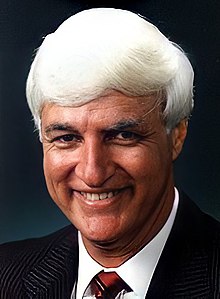

Bob Katter

Bob Katter | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1993 | |

| Father of the House | |

| Assumed office 11 April 2022 | |

| Preceded by | Kevin Andrews |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Kennedy | |

| Assumed office 13 March 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Rob Hulls |

| Leader of the Katter's Australian Party | |

| In office 5 June 2011 – 3 February 2020 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Robbie Katter |

| Member of the Queensland Parliament for Flinders | |

| In office 7 December 1974 – 25 August 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Bill Longeran |

| Succeeded by | Seat abolished |

| Minister for Northern Development; Community Services & Indigenous Affairs | |

| In office 7 November 1983 – 25 September 1989 | |

| Premier | Joh Bjelke-Petersen Mike Ahern Russell Cooper |

| Preceded by | Thomas Gilmore |

| Succeeded by | Martin Tenni |

| Minister for Mines and Energy | |

| In office 25 September 1989 – 7 December 1989 | |

| Premier | Russell Cooper |

| Preceded by | Martin Tenni |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Gilmore Tony McGrady |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Bellarmine Carl Katter 22 May 1945 Cloncurry, Queensland, Australia |

| Political party | Katter's Australian (since 2011) |

| Other political affiliations | National (until 2001) Independent (2001–2011) |

| Relations | Carl Katter (half-brother) Alex Douglas (nephew) Kim Hames (cousin) See Katter family |

| Children | Robbie |

| Parent(s) | Bob Katter Sr. Mabel Horn |

| Residence(s) | Charters Towers, Queensland, Australia |

| Education | Mount Carmel College St Columba Catholic College |

| Alma mater | University of Queensland |

| Occupation | Member of Parliament - Insurance, mining and cattle interests (Self-employed) |

| Profession | Farmer, Labourer and Politician |

| Website | www |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Australian Army Reserve |

| Years of service | 1964–1972[1] |

| Rank | Second Lieutenant |

| Unit | 49th Battalion, Royal Queensland Regiment |

Other offices

| |

Robert Bellarmine Carl Katter (born 22 May 1945) is an Australian politician who has been a member of the House of Representatives since 1993.[2][3] He was previously active in Queensland state politics from 1974 to 1992. Katter was a member of the National Party until 2001, when he left to sit as an independent. He formed his own party, Katter's Australian Party, in 2011.

Katter was born in Cloncurry, Queensland. His father, Bob Katter Sr., was also a politician. Katter was elected to the Queensland Legislative Assembly at the 1974 state election, representing the seat of Flinders. He was elevated to cabinet in 1983, under Joh Bjelke-Petersen, and was a government minister until the National Party's defeat at the 1989 state election.

Katter left state politics in 1992, and the following year was elected to federal parliament standing in the Division of Kennedy (his father's old seat). He resigned from the National Party in the lead-up to the 2001 federal election, and has since been re-elected four more times as an independent and another four times for his own party. Katter is known for his social conservatism.[4] His son, Robbie Katter, is a state MP in Queensland, the third generation of the family to be a member of parliament.[1]

Early life, education and career

[edit]Katter was born on 22 May 1945 in Cloncurry, Queensland.[1] He is the one of three children born to Mabel Joan (née Horn) and Robert Cummin Katter; his mother died in 1971 and his father had three more children with his second wife, including Carl.[5]

Katter's father was raised in Cloncurry where he ran a clothing shop and managed a local cinema. He was elected to Cloncurry Shire Council in 1946 and to federal parliament in 1966.[5] Katter is of Lebanese descent through his paternal grandfather Carl Robert Katter (originally spelled "Khittar"), who was born in Bsharri and immigrated to Australia with his parents in 1898. He was naturalised in 1907, after previously being refused naturalisation under the White Australia policy.[6]

Katter received his early education in Cloncurry, where he was one of only six at his school who finished year 12.[7] He attended Mount Carmel College in Charters Towers.[8] He went on to the University of Queensland, where he studied law, but later dropped out without graduating. While at university, Katter was President of the University of Queensland Law Society[9] and St Leo's College.[10] As a university student, Katter pelted the Beatles with rotten eggs during their 1964 tour of Australia, declaring in a later meeting with the band that he undertook this as "an intellectual reaction against Beatlemania".[11] He also served in the Citizens Military Forces, with the rank of second lieutenant.[12]

Returning to Cloncurry, he worked in his family's businesses, and as a labourer with the Mount Isa Mines.[7][13]

State politics (1974–1992)

[edit]

Katter's father was a member of the Australian Labor Party until 1957, when he left during the Labor split of that year. He later joined the Country Party, now the National Party. The younger Katter was a Country Party member of the Legislative Assembly of Queensland from 1974 to 1992, representing Flinders in north Queensland. He was Minister for Northern Development and Aboriginal and Islander Affairs from 1983 to 1987, Minister for Northern Development, Community Services and Ethnic Affairs from 1987 to 1989, Minister for Community Services and Ethnic Affairs in 1989, Minister for Mines and Energy in 1989, and Minister for Northern and Regional Development for a brief time in 1989 until the Nationals were defeated in that year's election.[1]

Katter was a strong supporter of Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen. In August 1989 he abruptly resigned from the cabinet of Bjelke-Petersen's successor Mike Ahern, along with fellow cabinet ministers Russell Cooper and Paul Clauson. Their resignation was reportedly an attempt to force Ahern's removal as party leader.[14] Bjelke-Petersen subsequently endorsed Katter to succeed Ahern as leader and premier.[15]

Katter returned to cabinet after only a month, following Cooper's successful ouster of Ahern in September 1989.[16] As mines minister, he was the subject of a no-confidence motion from the Queensland Chamber of Mines in November 1989, following his proposed changes to mining legislation that were perceived as favouring the interests of graziers over mining companies.[17] His term as a minister ended following the government's defeat at the 1989 state election.[18]

Federal politics (1993–present)

[edit]Nationals MP (1993–2001)

[edit]Following his father's retirement from federal parliament, Katter was an unsuccessful candidate for National Party preselection for the seat of Kennedy prior to the 1990 federal election..[19]

Katter did not run for re-election to state Parliament in 1992. He ran as the National candidate in his father's former seat of Kennedy at the 1993 federal election, facing his father's successor, Labor's Rob Hulls. Despite name recognition, Katter trailed Hulls for most of the night. On the eighth count, a Liberal candidate's preferences flowed overwhelmingly to Katter, allowing him to defeat Hulls by 4,000 votes.[20] He would not face another contest nearly that close for two decades.

In 1994, Katter advocated against the Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994,[21] a federal law that bypassed Tasmania's anti-gay laws,[22] claiming the government was "helping the spread of AIDS" and legitimizing "homosexual behavior". He also believed the laws jeopardized states' rights in Australia.[23]

Katter was re-elected with a large swing in 1996, and was re-elected almost as easily in 1998.[24] However, when he transferred to federal politics, he found himself increasingly out of sympathy with the federal Liberal and National parties on economic and social issues, with Katter being opposed to neoliberalism and social liberalism.[25]

Independent MP (2001–2011)

[edit]In 2001, Katter resigned from the National Party and easily retained his seat as an independent at the general elections of 2001, 2004, 2007 and 2010, each time ending up with a percentage vote in the high sixties after preferences were distributed.[26][27][28][29]

In the aftermath of the 2010 hung federal election, Katter offered a range of views on the way forward for government. Two other former National Party MPs, both independents from rural electorates, Tony Windsor, Rob Oakeshott[30] decided to support a Labor government. Katter presented his 20 points document and asked the major parties to respond before deciding which party he would support.[31] As a result, he broke with Windsor and Oakeshott and supported the Liberal/National Coalition for Government. On 7 September 2010, Katter announced his support for a Liberal/National Party coalition minority government.[32]

Katter's Australian Party (2011–present)

[edit]On 5 June 2011, Katter launched a new political party, Katter's Australian Party, which he said would "unashamedly represent agriculture".[33] He made headlines after singing to his party's candidates during a meeting on 17 October 2011, saying it was his "election jingle".[34]

In the 2013 election, however, Katter faced his first serious contest since his initial run for Kennedy in 1993. He had gone into the election holding the seat with a majority of 18 percent, making it the second-safest seat in Australia. However, reportedly due to anger at his decision to back Kevin Rudd (ALP) for Prime Minister following Julia Gillard's (Prime Minister) live cattle export ban (Rudd, within weeks, reopened the live export market), Katter still suffered a primary-vote swing of over 17 points. His name heavily associated with Rudd. In the end, Katter was re-elected on Labor preferences, suffering a two-party swing of 16 points to the Liberal National party.[35][36]

In the 2016 election, Katter retained his seat of Kennedy, with an increased swing of 8.93 points toward him.[37]

On 15 August 2017 Katter announced that the Turnbull government could not take his support for granted in the wake of the 2017 Australian parliamentary eligibility crisis, which ensued over concerns that several MPs held dual citizenship and thus may be constitutionally ineligible to be in Parliament. Katter added that if one of the affected MPs, Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce, lost his seat, the Coalition could not count on his support for confidence and supply.[38]

In November 2018, Katter secured funds for three inland dam-irrigation schemes in North Queensland.[39]

In the 2019 election, Katter was returned to his seat of Kennedy with a swing of 2.9 points towards him, in spite of an unfavourable redistribution of his electorate.[40] In the 2022 election, he was re-elected again, and became the Father of the Australian House of Representatives following the retirement of Kevin Andrews.

In July 2024 it was announced that a portrait of Katter may be commissioned and hung in the Federal Parliament.[41]

Political views

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Australia |

|---|

|

Katter is known as an unabashed social conservative and agrarian socialist.[42] Like his father, his views on economic matters echo 1950s "Old Labor" policy as it was before the 1955 DLP split. He opposes privatisation and economic deregulation and strongly supports traditional Country Party statutory marketing.[citation needed] In an interview in 1994, he cited his political heroes as ALP figures Jack Lang and Ted Theodore and U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt, but said Lang was ultimately a failure and he was "aiming to be a John McEwen".[43] The sobriquet 'Mad Katter' was coined by his opponents to describe his nationalistic developmentalism.[44][45][46]

As of 2020, Katter described himself as belonging to the "hard left," citing his continuing membership of the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union.[47][13] In a 2022 interview with The Chaser, Katter claimed that he had never pledged allegiance to the Queen of Australia when entering parliament.[48]

Abortion

[edit]In 1980, Katter seconded a motion by Don Lane calling on the Queensland state government to "protect the lives of unborn Queensland children being killed by abortion".[49]

In 2006, Katter voted against a federal bill which would increase the availability of abortion drugs.[50]

Environment

[edit]Katter has opposed enacting climate change legislation to control emissions.[51] He advocates for measures that reduce carbon footprints.[52] Katter has championed the mandating of ethanol fuel content. He has additionally pioneered protests against imported bananas, and is an opponent of the concentration of the Australian supermarket industry amongst Coles and Woolworths.[53]

Gun laws

[edit]An opponent of the tougher gun control laws introduced in the wake of the 1996 massacre in Port Arthur, Tasmania, Katter was accused in 2001 of signing a petition promoted by the Citizens Electoral Council (CEC), an organisation that claims the Port Arthur massacre was a conspiracy. He has stated that he always and still believes there was no conspiracy.[54]

Immigration

[edit]In 2017, Katter called for a "Trump-like travel ban" in Australia after a New South Welshman was arrested on terrorism charges.[55] That same year, Katter repeated a pledge used by the far-right organisation "Proud Boys", including that he was "a proud western chauvinist". When asked about the incident when it was publicised in 2019, Katter distanced himself from the group, saying "I don't know who this group is or anything about it".[56][57]

Indigenous Australians

[edit]In 1987, as Queensland minister for Aboriginal and Islander affairs, Katter credited the state government with reducing Aboriginal deaths in custody by introducing "new detention procedures to divert people arrested for minor offences away from traditional custody after a three-hour cooling off period".[58] In 1989 he opposed installing condom vending machines in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to reduce the spread of AIDS, describing the plan instead as an attempt at eugenics, or "racist genocide".[59]

Katter is also an opponent of voter identification laws, denouncing the Coalition's proposed introduction of them in 2021 as a racist system that would disenfranchise Aboriginal communities.[60] In 2022, he announced that would not support an Indigenous Voice to Parliament proposal, but did believe that the indigenous people of Australia deserved a referendum on how they should be represented in parliament.[61]

North Queensland statehood

[edit]

Katter supports North Queensland statehood.[63]

LGBT rights

[edit]In November 1989, Katter claimed there were almost no homosexuals in North Queensland. He promised to walk backwards from Bourke across his electorate if they represented more than 0.001 percent of the population.[64][65] Katter also said "mind you, if there are more, then I might take to walking backwards everywhere!" Katter voted against the Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act, 1994 (Cth), which decriminalised homosexuality in Tasmania.[66] He does not support same-sex marriage.[67] His response to the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey result was the subject of international attention, as in response he declared that the issue of crocodiles killing people in North Queensland was more pressing than same-sex marriage. Therefore he declared that "I ain't spending any time on it!" on the latter issue.[68] In December 2017, Katter was one of only four members of the House of Representatives to oppose the Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Bill 2017 legalising same-sex marriage in Australia.[69]

Personal life

[edit]Katter occasionally identifies as being an Aboriginal Australian and has described himself as a blackfella in federal parliament, in interviews, during television appearances and at public events.[70][71][72][73][74] Katter claims that in his youth he was accepted as a member of the Kalkadoon tribe in the Cloncurry area, otherwise known as the "Curry mob", and said he has long since felt a deep connection with Aboriginal people.[71][75]

His son Robbie has been a member of the Queensland Legislative Assembly since 2012, representing Mount Isa from 2012 to 2017, and Traeger since 2017.[76] He represents much of the territory that his father represented in state parliament.

Katter supports the North Queensland Cowboys in the National Rugby League (NRL).[77][78]

Bibliography

[edit]- Katter, Bob (2012). An Incredible Race of People. Sydney: Pier 9 Books. ISBN 9781742665818. OCLC 795963853.

- Katter, Bob (2017). Conversations with Katter. Foreword by Elliot Hannay. Chatswood: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781921024399. OCLC 1023617539.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "The Hon. (Bob) Robert Carl Katter". Senators and Members of the Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Round About WITH PENELOPE". Sunday Mail. No. 788. Queensland, Australia. 27 May 1945. p. 7. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Bob Katter Fact Check: never heard of Gays before 50? Archived 27 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine", QNews, January 2019.

- ^ Murray, Duncan (21 April 2022). "Maverick MP Bob Katter blows up over China in Q&A appearance". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b Williams, Paul D. (2007). "Katter, Robert Cummin (Bob) (1918–1990)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 17. Melbourne University Press.

- ^ Pringle, Helen (27 August 2018). "'The crimson thread of kinship runs through us all': Bob Katter and the colour of Australian law". ABC News. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ a b Nowra, Louis, "The Heart and Mind of Bob Katter Archived 28 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine", The Monthly, April 2013.

- ^ Crockford, Toby; Holdsworth, Matty (12 June 2023). "Old school ties: Where Qld powerbrokers went to school". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ "Past Presidents — The University of Queensland Law Society Inc". The University of Queensland Law Society. The University of Queensland Law Society Incorporated. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Katter, Hon Robert Carl (Bob)". Former Member Biography. Queensland Parliament. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Townsend, Ian (30 June 2004). "I am the egg man: Katter". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Australia. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

aphbiowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Katter, Bob (31 October 2016). "Katter: almost a death a week on a construction site in Australia and you want to crucify the CFMEU?". Archived from the original (Press Release) on 16 April 2020.

- ^ "Nationals commit suicide in Qld". The Canberra Times. 29 August 1989.

- ^ "Katter best suited: Sir Joh". The Canberra Times. 29 August 1989.

- ^ "Cooper's Cabinet: 4 sacked". The Canberra Times. 24 September 1989.

- ^ "Mines chamber calls for Minister's sacking". The Canberra Times. 24 November 1989.

- ^ "'Useless rubbish' on the way out". The Canberra Times. 5 December 1989.

- ^ "Katter misses choice for father's seat". The Canberra Times. 15 January 1990.

- ^ "Division of Bowman". Federal election, 1993. Adam Carr. 13 March 1993. Archived from the original on 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994 – Sect 4". Commonwealth Consolidated Acts. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ Tasmania at the time had the world's harshest anti-homosexuality laws. Croome, Rodney (12 April 2014). "Gay activists fought a public battle for private rights". The Mercury. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 28 November 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Peake, Ross, "Row ahead: Libs back gay stance Archived 14 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine", The Canberra Times, Fri 23 Sep 1994, page 1.

- ^ Carr, Adam. "1998 Qld House of Representatives Results". Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

- ^ Raue, Ben (6 June 2011). "Bob Katter launches new political party". The Tally Room. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Carr, Adam. "2001 Qld House of Representatives Results". Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

- ^ Carr, Adam. "2004 Qld House of Representatives Results". Archived from the original on 26 August 2015.

- ^ Carr, Adam. "2007 Qld House of Representatives Results". Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

- ^ Adam, Carr. "2010 Qld House of Representatives Results". Archived from the original on 21 February 2018.

- ^ Foley, Meraiah (25 August 2010). "Rural Lawmakers Hold Key in Australian Election". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Rodgers, Emma (3 September 2010). "'Potent' Katter's arm twisted by Rudd". ABC News. Australia. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Saulwick, Jacob; Davis, Mark. "Katter supports Abbott". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ Marszalek, Jessica (5 June 2011). "Katter's party to 'unashamedly represent agriculture'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ "Katter puts the fun into party briefing". Herald Sun. Australian Associated Press. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ "LNP still hopeful of taking Katter's seat". 9 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013 – via www.abc.net.au.

- ^ "Katter in clear" Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, northweststar.com.au. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Kennedy". Australian Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Bickers, Claire; Le Messurier, Danielle (15 August 2017). "Katter refuses to guarantee support". The Courier Mail. News Corp Australia Network. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Morrison spends $200m to nail down Bob Katter's support for minority government". TheGuardian.com. 8 November 2018. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Kennedy, QLD - AEC Tally Room". Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Crotty, Gemma (2 July 2024). "Qld MP Bob Katter set to be honoured with official portrait in Parliament House to commemorate 50 years of service". Sky News. Archived from the original on 5 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Syvret, Paul (19 December 2011). "Bob Katter's parallel universe: He's really a socialist". The Courier Mail. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Grose, Simon (21 May 1994). "Motormouth messiah from the Deep North". The Canberra Times.

- ^ Chvastek, Nicole (25 August 2010). "The Mad Katter .. and the Frankston Eviction Debacle". ABC Radio. Australia. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Birmingham, John (24 August 2010). "The joys and pains of a well hung parliament". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Steven; Ironside, Robyn (25 August 2010). "Mad Katter denies kill threat". The Advertiser. Australia. Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Interview with Bob Katter: "‘Everyone tells me I’m crazy, and I actually am’: Katter" Archived 24 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Sky News, Feb 16, 2020.

- ^ Puglisi, Leonardo (18 October 2022). "Bob Katter 'confesses he refuses to pledge allegiance to the Queen' in interview with The Chaser". 6 News Australia. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Qld abortion motion". The Canberra Times. 14 March 1980.

- ^ "Katter to oppose abortion drug bill". ABC News. 14 February 2006. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Katter throws crocs into climate debate". ABC News. Australia. 12 August 2009. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ Katter's Australian Party (25 August 2011). "Another milestone for clean energy corridor". Australia. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ Harvey, Michael (23 August 2010). "Six men who could hold the key to Australia's government". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Katter accused of promoting Port Arthur massacre conspiracy theory". ABC News. Australia. 20 June 2001. Archived from the original on 19 July 2001. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Bob Katter calls for Trump-like travel ban". Chronicle. 1 March 2017. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Bob Katter pledges allegiance to far-right group but dismisses it as 'larrikinism'". the Guardian. 9 June 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Bob Katter has pledged allegiance to the far-right group Proud Boys in a YouTube video". SBS News. Archived from the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Ministers agree to divert Aborigines away from hails". The Canberra Times. 11 September 1987.

- ^ Condom Decision "Racist Genocide Archived 22 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine", Strait Talking, Torres News (Thursday Island, QLD), Thu 24 Aug 1989.

- ^ Barton, Fraser (12 November 2021). "Bob Katter slams 'racist' voter ID laws". The New Daily. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Clarke, Harry (30 November 2022). "Bob Katter weighs in on proposed Voice to Parliament". Country Caller. Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ 7News Gold Coast (27 October 2020). "Bob Katter reveals potential flag design for North Queensland". Facebook. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[better source needed] - ^ Dale, Allan (5 May 2015). "North Queensland's powerful trio will shake up the state". The Conversation. New northern allies. Archived from the original on 2 August 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

In a vast state governed from the south-east capital of Brisbane, north Queenslanders have historically struggled to have their concerns heard and taken seriously – so much so that federal MP Bob Katter and others have long pushed for north Queensland to become its own state.

- ^ Seccombe, Mike (4 March 1994). "Bottom Line For Katter". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 2. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ Wright, Tony (24 August 2011). "No gays, Bob? Try closer to home". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Roberts, Greg (1 April 2000). "Katter-brained". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 42.

- ^ "Gay marriage ridicule 'damages youths'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ "Bob Katter's Rant About Same Sex Marriage And Crocodile Attacks Is Going Viral". Triple M. 20 November 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ "House of Representatives Hansard THURSDAY, 7 DECEMBER 2017". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Baker, Mark (6 April 2013). "Lone ranger". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

One of Bob Katter's greatest passions is the plight of indigenous Australians. "I identify with them. I'm not white and I come from Cloncurry. I'm not too sure where my racial background has come from but I am not going to argue if someone calls me a blackfella. I'm not going to argue that I am not", he says.

- ^ a b "Palm Island Indigenous Leaders' Forum: "Dis mah lan"". Bob Katter. Katter's Australian Party. 27 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

"We from Cloncurry call ourselves the Curry mob, we come from the Kalkadoon heritage"

- ^ "Ministerial Statements: Closing The Gap". Parliament of Australia. Australian Government. 14 February 2017. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

All of my life I have been called a blackfella. I take great pride in being identified that way and have identified that way on numerous occasions. We Cloncurry people call ourselves the 'Curry mob', and there is a bit of everything in the family tree. None of us look too black and none of us look too white!

- ^ Reynolds, Emma (4 July 2017). "Viewers confused as Bob Katter reveals he 'identifies as a blackfella on occasion". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

Asked about land title, he replied: "I identify as a blackfella on occasion and I'll identify this time as a blackfella — we are the most land-rich people on Earth, we blackfellas in Australia, and we are not allowed to use it. We are not allowed to have a title deed..."

- ^ Butler, Dan (22 April 2022). "Bob Katter again claims Aboriginality on Q&A". NITV News. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022.

While discussing the plight of the Murugappan family from Biloela and refugees policy more broadly, Katter referred to himself as a "Blakfulla". "I come from Cloncurry and I'm dark - I'm one of the Curry mob, you know? We made a hell of a bad mistake 150 years ago, letting you whitefellas in. I don't know that we should make the same mistake again."

- ^ Calcino, Chris (5 July 2017). "Bob Katter explains 'blackfella' heritage after QANDA confusion". Cairns Post. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

"I lived out bush with First Australians in my mining days and many other roles… mustering cattle and those sort of things," he said. "Under the law, if you lived in an area and were accepted as part of a tribe in that area, you legally would be part of the tribe. I claim the law." Mr Katter said he had long felt a deep identification with Aboriginal people. "I come from Cloncurry, we always refer to ourselves as 'Curry mob'," he said. "In that situation, I identified very strongly with my cousin-brothers."

- ^ "Traeger - QLD Electorate, Candidates, Results". abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Archived copy". Facebook. Archived from the original on 12 May 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "A message to the NQ Cowboys from Bob Katter". Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

External links

[edit]- 1945 births

- Independent members of the Parliament of Australia

- Katter's Australian Party members of the Parliament of Australia

- Australian monarchists

- National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia

- National Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Queensland

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Kennedy

- People from Cloncurry, Queensland

- Members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly

- Living people

- Australian Roman Catholics

- Australian nationalists

- 21st-century Australian politicians

- 20th-century Australian politicians

- Australian people of Lebanese descent

- Australian political party founders